A dive into the interesting phenomenon of mixed-race people living in Japan, based on my own experience.

It is highly likely that you have heard of the superstar tennis player Naomi Osaka who at age 22 has recently become the highest compensated female athlete in the world. How about Denny Tamaki, the governor of Okinawa? What about Priyanka Yoshikawa who was crowned Miss World a few years ago or the famous baseball player Yu Darvish? What do they all have in common? Well, all of these people are considered in Japan to be hāfu (ハーフ in Japanese).

While most people falsely tend to think of Japan as a country that is completely homogeneous, Japan is actually home to a growing segment of foreigners and an even faster-growing population of mixed-race people. Many of these diverse citizens who are born to a Japanese parent and a non-Japanese parent have come to be known in Japan as hāfu, a romanized term of the English word “half.”

This label is, however, not used to refer to all people who are of mixed-race. Rather it is usually only reserved to describe those who are born to a Japanese mother or father whose other parent is from the West typically with roots in either Europe, North America, or South Asia. While there are certainly exceptions, Japanese people have not necessarily accepted the idea that all people who are of mixed-race deserve the title of hāfu, as they believe that this term does not fit for those born to a Japanese parent and someone with an ethnic heritage from the northern part of East Asia.

The interpretation of the racial description hāfu only applies when someone has physical features that obviously indicate their mixed heritage, especially in terms of skin color, a longer nose, larger eyes, or lighter hair. While this is somewhat of a gray area, those who are born to a Japanese parent and an Asian parent from a country where people look particularly different from those with classic Japanese features such as Thailand or India would, indeed, be referred to as hāfu. On the other hand, someone with a Japanese parent and a parent from China or South Korea would, most likely, not be considered as hāfu, because of the racial similarities among Japanese, Chinese, and Korean people. “I wouldn’t say that I think I am necessarily viewed as hāfu, but I do think some people will see me as a foreigner because I may resemble someone who is from China instead of Japan” (Ann-Li Hitosugi, Singapore/ Japan).

How many hāfu live in Japan?

While there are no statistics about the overall number of hāfu in Japan, the Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare has reported that each year approximately 36,000 children are born in Japan into families with one non-Japanese parent. That’s actually equivalent to about 1 in every 30 births. The data are, however, not broken down by ethnicity, and the majority of this group have a parent from either China or South Korea. We can, therefore, really only make “back of the envelope” estimates. Thus, the number of hāfu is still probably pretty low–perhaps approximately 5,000 births per year. These numbers have, however, been steadily increasing since just after WWII. Although there are probably about 100,000 people globally who fit these criteria, perhaps only 50,000 reside in Japan.

What is it like being hāfu?

I am actually hāfu, as my mother is Japanese and my father is a typical Caucasian American. I spent part of my childhood in both Japan and the U.S, and, although I never gave much thought about my mixed-race heritage while living in the States, I was reminded daily of my status as hāfu while growing up in Japan. Curiously and somewhat unconsciously, I have always tended to gravitate toward others in this rather unusual minority of people living in Japan. Like any minority, hāfu do face a certain degree of discrimination in Japan, but there are also many benefits of being hāfu. I will share both my personal experience and some comments from fellow hāfu.

Growing up as hāfu in Japan has been quite satisfying, as it provided me with a unique cultural identity and many opportunities to communicate with and meet all sorts of people. Being part of both Japanese and American cultures, I was often called upon to act as a cultural interpreter of all things Japanese to visitors from overseas. Conversely I was able to assist many Japanese to improve their proficiency with the English language. Based upon my own experience, the benefits of being hāfu in Japan certainly outweigh the short-comings.

As I am still relatively young, most of my experience has been based on my time as a student. Like a number of younger hāfu in Japan, I attended an international school in Tokyo. The curricula at these schools are, for the most part, taught in English, and the school year begins in August and goes until June much like schools in the West. (The Japanese educational system has thus far operated on an April to March schedule, although due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, it is highly likely that the academic year may soon change to conform to the Western schedule.) Most hāfu attending international schools spend most of their time with other kids who are also hāfu or children of ex-pats attending these schools. Some start out attending regular Japanese schools but end up transferring to an international school after a few years.

What are the benefits of being hāfu?

As mentioned above, one of the more obvious benefits of being hāfu is often language ability–especially with English. Hāfu children typically grow up speaking both Japanese and another language proficiently. Some learn to speak not just two but even three or four languages, making it easy to communicate with others. Such language skills can certainly come in handy when searching for a job, as many businesses are eager to employ people who are able to communicate so effectively.

Besides language skills the ability to bridge multiple cultures is what can give hāfu a true advantage. Familiarity with both Japanese and a foreign culture can make it possible for hāfu to be able to act as a “middle-man,” a soft skill in high demand by many employers. Such expertise can be applied from the boardroom to the front lines of a retail store facing an ever-increasing number of foreign tourists (assuming that in-bound travel to Japan will bounce back after the coronavirus crisis subsides.)

One of the more practical benefits of being hāfu can include being a dual-citizen of both Japan and another country. Such status allows hāfu to travel back and forth for business or to visit their family and friends without having to get a visa in each respective country. Especially considering the restrictive immigration policies of some countries, having a dual-citizen on staff can be an especially attractive benefit for an employer. There is, however, a caveat, as the official rules in Japan stipulate that all dual-citizens are supposed to declare their allegiance either to Japan or another country when they reach age 22. This policy is, however, rarely enforced which makes it possible for dual-citizens to retain both of their passports indefinitely.

Ever since Westerners started to come to Japan, many Japanese people have taken a strong interest in them. Because Japanese society is more cosmopolitan than ever, foreign tourists are now nothing out of the ordinary–at least in Tokyo. Many more western-looking hāfu are often mistaken as visiting tourists. While this tendency can certainly be quite frustrating at times, it is important to remember that this is often just an innocent mistake.

In general, while there may be a decent amount of shortcomings that may come along with being hāfu in Japan, being hāfu is truly a wonderful and unique experience. You are able to represent two different countries and learn about the culture of both of them. The many benefits of being hāfu certainly outweigh the shortcomings in the long run.

What are the short-comings of being hāfu?

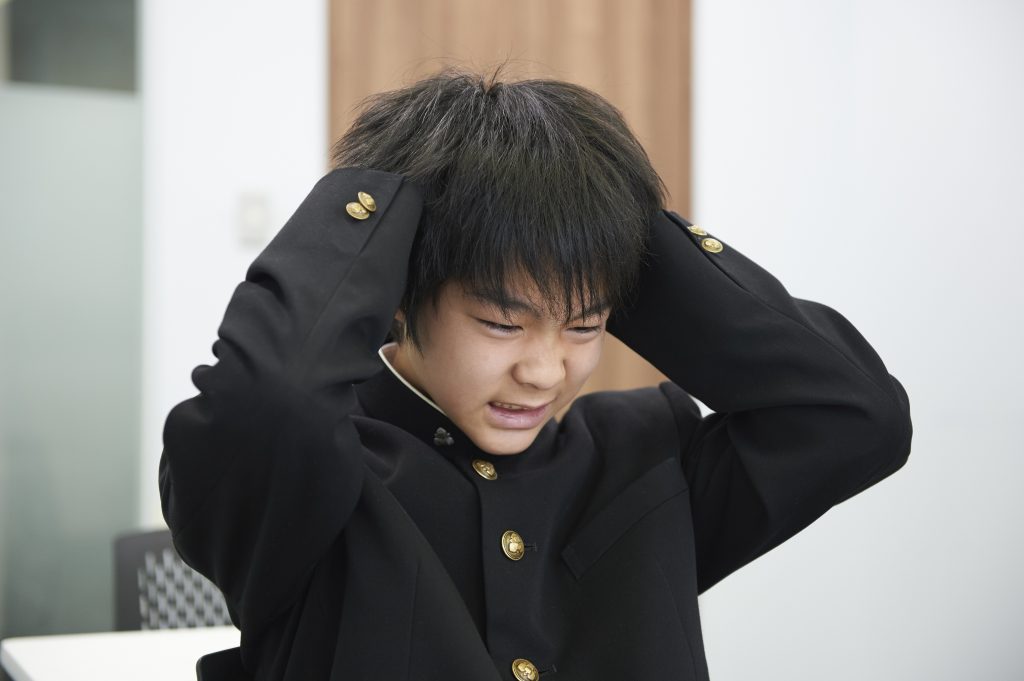

Something that has always been a part of Japanese culture is the sense of being “in-line” with everyone else. Japanese culture has never been particularly forgiving of those who step out of that line or, in other words, do something different from everybody else. The Japanese phrase “the nail that sticks out shall be hammered down” (出る釘は打たれる) is, in fact, well known throughout the world. For the hāfu minority, being “called out” as different and subsequently being “hammered down” both figuratively and sometimes literally is just part of everyday life.

Something that many hāfu children tend to face when growing up in Japan is bullying. This is because they are a natural target, simply because hāfu children look different from their Japanese schoolmates. The phenomenon of the bullying and racial discrimination of hāfu children is, however, somewhat complicated. It is rooted in jealousy. Japanese kids typically consider hāfu children to be especially “lucky” and good looking. Thus, being the cause for some hāfu children to feel uncomfortable in the public schooling system. “I seemed to get more looks or stares from those around me when I was attending a public elementary school in Japan. I felt much more comfortable being around other hafu when attending an international school” (Ayana Nakamichi, Japanese/ Pakistani).

Generations of Japanese advertising has solidified the common belief in Japan that Westerners–especially those with typically Nordic features such as blonde hair–are more attractive. Such aspirational images are, though, clearly considered to be extremely foreign and are, therefore, somewhat out of reach. Hāfu exhibit, on the other hand, a mixture of such attractive characteristics combined with a touch of more familiar Japanese facial features. To the Japanese this combination can make hāfu seem quite exotic and the object of fascination.

The media reinforce these beliefs. While there are many famous actors and models (known as geinojin (芸能人) in Japan) who are Asian, some of the most popular geinojin who are praised for their good looks are, in fact, hāfu. School children adopt this thinking from their parents and from being bombarded by such messaging across multiple media. Some of these kids in turn become jealous of hāfu children who are ridiculed simply due to their appearance.

Jealousy of hāfu is, however, not just limited to outward appearance. It is often related to the fact that many hāfu grow up being bilingual. Since all hāfu children have at least one parent who is from a foreign country, most hāfu are raised in homes in which both Japanese and a foreign language are spoken. Especially when that foreign language is English, hāfu typically have a natural leg up on their Japanese counterparts who typically struggle to learn English in school.

This phenomenon may seem difficult to accept, but English language proficiency is a sensitive issue in Japan. You have to remember that Japanese schoolchildren routinely bully their own countrymen who come back to Japan as kikokushijo (帰国子女) or returnees from living abroad partially from resentment of their language skills. Thus, it is relatively easy to see how hāfu who look a little different and often have a foreign-sounding name would become a natural target.

The issue with the term “hāfu“

The main problem with the actual term of hāfu is due to the fact that many people who are indeed mixed, do not view themselves as half of another culture and rather view themselves to be 100% of both. While this may be sort of hard to wrap your head around, the term hāfu can sometimes have a negative connotation when used to describe certain people since these people take it as though people do not believe that they are fully Japanese even if they have grown up their whole lives in Japan and are native speakers of the language. In order to combat this problem, many hāfu and people around Japan have started to incorporate using the term “double” instead of “half” in order to signify that they are not half of the culture but are made up of two full parts. I too am in support of this change but due to the term being established into the Japanese vocabulary for such a long time it may take a while until this term starts to be used.

Can someone who is hāfu be mistaken for a foreigner?

Some hāfu appear more “foreign” or western-looking, whereas others can pass easily as “full” Japanese. Despite the fact that many were born in Japan and have never lived abroad, sometimes hāfu will be treated in public as a foreigner. “It’s annoying how a lot of times when I go to a restaurant the waiter will bring me a fork and knife on the side in addition to chopsticks or an English menu” (Koa Kellenberger, Japanese/ American).

Overall take on being hāfu in Japan

While not all hāfu are destined to become as famous as Naomi Osaka or Yu Darvishsefat, there are more and more of us, and we’re playing an increasingly important role in Japanese society beyond the world of sports and acting. It is significant that Priyanka Yoshikawa has gone on to become an entrepreneur and the CEO of the new cosmetics company Mukoomi in Japan and that Denny Tamaki was the first hāfu member of the Japanese House of Representatives and is now the governor of Okinawa. These milestones are helping to solidify the foothold of hāfu in a more global Japan which is becoming ever more westernized.

While you can always see “the glass as half empty,” growing up in Japan as hāfu has definitely made me see “the glass as half full” or in my case “hāfu full.” I am proud of my unique heritage which provides many opportunities and offers an amazing look on life. Japanese people are starting to become more and more accustomed to hāfu and are becoming more welcoming of their fellow countrymen with a mixed racial background.

While I am accepting of the term hāfu, I would feel more comfortable with the label “double,” as I see myself as being truly 100% Japanese and American. Rather than get stuck on semantics, I am, though, most encouraged by the fact that hāfu in Japan are here to stay, and we are becoming ever more accepted in Japanese society.

Related Articles

AI Girlfriends: Exploring the World of Virtual Companions

AI-generated girlfriends are growing popular on Japanese Twitter. Learn more about what they can do, and what it could mean for the future.

Discover Japan’s Top 10 Must-Visit Places

From stunning landscapes to bustling cities, Japan offers many unforgettable experiences. Here are Japan’s top 10 best places to visit!