Practical advice for mastering Japanese from a 30+ year veteran student of the language.

“So, you want to learn Japanese?” That was exactly the question posed in halting English by my very first Japanese instructor as a first-year college student during what now seems like a lifetime ago. Japan’s now-infamous asset price bubble had just gotten started a few months earlier, Mitsubishi Estate was gearing up to purchase the iconic Rockefeller Center in New York, and at the time it seemed like the country was on a path of total global domination. Thus, although my interest in Japan was initially kindled many years before by the friendship of my grandfather with a Japanese family that dated from right after WWII, I was hardly alone in that Japanese 101 class filled with more than forty eager initiates who were keen to get a piece of the action of Japan’s widely publicized ascent fueled by a rapidly appreciating yen. On that first day of class, our teacher wanted, though, to make certain that we were, in fact, truly committed. She knew that most of us were not up to the task, and the attrition rate after the first semester would be high. Thus, she followed that opening salvo with an extended pregnant pause.

Are you committed?

As a highly impressionable 18-year-old student, I, along with my fellow Japanese novices, belted out the obvious, “Yes, that’s why we’re here! Let’s get going!” Our instructor shrugged and immediately shifted into what, at the time, was utterly incomprehensible Japanese and proceeded to introduce the concept of hiragana and katakana, two of Japan’s three “alphabets.” We somehow came to understand that she expected us to memorize all 46 katakana “letters” by the next day – when we would be taking up their phonetic equivalents in hiragana. She went on to inform us that from Day 3, we would begin to learn how to read and write Japanese kanji characters, the pictograms derived from Chinese that are used in conjunction with phonetic “letters.” As approximately 2,500 of these characters are used in modern Japanese, our teacher must have figured that we would all be better off the sooner we started. These seemingly impossible tasks took us all by surprise but hammered home the need to be utterly committed if we were going to master the language.

If you are now in a similar position, first, I encourage you to be completely honest with yourself about what you have signed up to do. You must be sure of your appreciation of the long-term commitment necessary to learn Japanese. Hey, don’t be scared; I have confidence in you! Let’s assume, therefore, that you have the self-discipline to make a go of it.

You may never become truly fluent…

But not so fast! Now more than 30 years after that fateful day and after spending more than 20 years living, studying, and working in Japan, I can honestly tell you that no matter how diligently you strive to improve your Japanese, you may never become truly fluent. What? Did he just say “never?” There are those for whom the ability to converse in Japanese comes relatively naturally, but real fluency seems to require one to be born into the culture and raised in Japan. Don’t become discouraged, though, as even after learning a few basic phrases, your Japanese friends and acquaintances will actively praise your language ability and encourage you to learn more. Particularly if you are from the West and, therefore, have a native language that is entirely different from Japanese, you, too, can develop into a proficient Japanese speaker with enough effort. I just want to remind you that it won’t be easy.

Practical Advice

Okay. Let’s get down to business. What practical steps do you need to take to achieve at least a base level of fluency? You can boil down the essential elements to just three components: the right environment for learning, talented teachers, and proactive use of essential tools.

1. The Right Atmosphere

Before ever setting foot in Japan, I spent approximately one year in a rural setting in New England learning the basics of Japanese while taking plenty of other classes as a college freshman. With two semesters under my belt, I thought that I was making reasonably good progress and, naturally, could not wait for an opportunity to practice my new language skills on the ground in Japan. I was, however, not prepared for the shock of arriving in Tokyo’s steaming hot summer for the fall semester of my second year only to find that I could barely communicate! It seemed as though everyone was speaking so quickly, and I could only decipher about one out of every twenty kanji characters, which, essentially, rendered me illiterate! I quickly realized that learning a foreign language is not something that can be done on a part-time basis and that there are, in fact, many benefits to total immersion. I did, however, start to pick up more and more just by being in Japan, and I lucked out by being placed for a short-term stint with a wonderful Japanese homestay family in Tokyo.

2. Consider trying a homestay…

My homestay “mother” made it her mission in life to get me up to speed as quickly as possible. She even put labels on almost everything in their house to encourage me to learn new vocabulary. All of this attention was a little overwhelming at first, but now I realize just how lucky I was to have had this experience in an environment truly conducive to learning. I was even able to ask to extend my stay at this home for another year while I commuted to a Japanese university in Tokyo as an exchange student. Although the opportunity to live together with a Japanese family is not possible for everyone and comes along with certain restrictions, which may seem a little constraining for college students, if you get a chance to do so, try it!

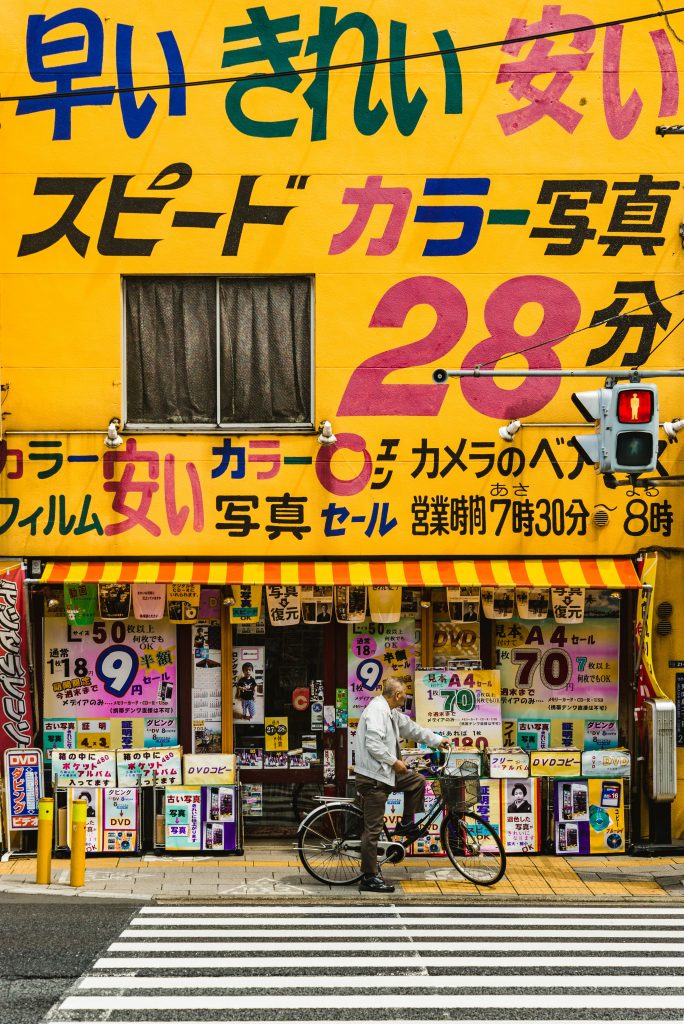

3. Get out of Tokyo!

There is no doubt that living in Tokyo can be exciting—especially for a young adult. The hyper-stimulation of life in the world’s largest metropolitan area can, however, easily distract you and make it difficult to concentrate on your studies. While you will miss out on a lot, especially for native English speakers, it is, moreover, possible to survive in Tokyo without learning any Japanese which is precisely the problem. If you are serious about trying to jump start your language proficiency with a true total immersion experience, then the Japanese countryside is the place to go.

Immediately after graduation from college I was lucky enough to receive a scholarship from the U.S. government to attend graduate school in Japan. While I could go to virtually any public institution in the country, the one stipulation was that it had to be a national university outside the big city centers of Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya. At that point, as I had never been farther west than Hiroshima, on a whim I choose Kyushu University in Fukuoka. This turned out to be a great choice, as I quickly learned that English does not get you very far outside Tokyo.

While things in Hakata, the central part of Fukuoka, had become much more international in the decades since when I first touched down at Fukuoka Airport. At the beginning of the summer of 1990, there were virtually no bilingual signs, and very few people could converse in English. I knew not a soul in town, and it was hotter than hell. All I had was the name of the instructor assigned to oversee my year-long grant. It turns out that I arrived just as the rainy season ended at the beginning of summer break. I somehow found the office of my instructor. I was greeted warmly before being told that all of the students had just left to go home like he was preparing to do, there would be no classes for almost three months, and I should just spend this time getting comfortable living in Kyushu. Thus, I was all on my own and would just have to survive the long summer in a land where I would be forced to communicate only in Japanese. As this “trial by fire” was initially quite challenging, in retrospect, my year as a graduate student at Kyushu University proved to be a great way to gain confidence and accelerate my Japanese language skills. This chance to live in Kyushu also ended up being fortuitous, as more than three decades later, I ended up deciding to relocate permanently to the island and now intend to stay forever.

4. Seek Talented Teachers

While being in the right environment helps you to stack the deck in your favor, finding the right teacher is the key to success. This is, naturally, “easier said than done,” but anyone serious about learning a foreign language can benefit from the guidance of a good coach. Checking the reputation of a specific language program or even a particular instructor by word of mouth is an excellent way to begin. While face-to-face instruction always seemed to work best for me, especially in the era of the ongoing coronavirus, now on-line teachers may also be a viable option. In addition to being safer, distance or e-learning may be more cost-effective. It is, however, best to expand the traditional definition of “teacher” in this case. If you are in an appropriate environment, then you can and should seek to learn from all sorts of people.

Especially if you are first able to make it to Japan, then you can learn from everybody. Japanese people are, in general, eager to help foreigners who demonstrate a desire to learn at least some of their language. You just need to get up enough courage to ask for help. Much of this type of learning leaves a strong impression. If you are taught, for example, how to order something unusual at a restaurant, you will, most likely, remember the experience forever.

5. Search for non-traditional opportunities to learn

In addition to regular language schools, you can find plenty of alternative classes, many of which may be quite inexpensive or even free. While I benefited from many years of formal instruction in a traditional classroom setting, one of the most useful courses that I ever took was an eight-week session on how to read Japanese newspapers that were offered for free in Yokohama. I was the only Westerner in that class in which all of the other students were from China and, therefore, had a definite advantage when it came to reading Chinese characters. I do not recall ever learning so many kanji in such a short period! Similar free or low-priced courses taught by volunteers are offered by municipal government offices all over the country.

6. Language Exchanges

Formal or informal language exchanges can sometimes be effective. This is when you essentially barter with a Japanese friend who would like to learn your native language. If you are a native English speaker, it should not be too difficult to find someone who may be interested in this sort of deal. The key is, though, to ensure that the language exchange be equitable with an equal amount of give and take by both parties. Who knows? Such an arrangement could lead to finding a romantic partner, as well.

7. Learn from your peers

While both of you may be prone to making the same mistakes, another type of teacher that may not be all that obvious is a peer. A couple of weeks into my first semester at Kyushu University, I met one of the only other Western graduate students. He was from Denmark. While we could have communicated in English, the two of us made a pact only to speak to each other in Japanese. As you can imagine, this must-have sounded pretty odd to our Japanese colleagues who overheard us conversing together on our own, but it helped both of us to reinforce what we were learning and build our vocabulary. We remain friends to this day!

Getting into the right environment and finding talented teachers will help you to become fluent. But at the end of the day, how hard you work and implement the tools and resources at your disposal is critical.

8. Vocabulary, vocabulary, vocabulary…

Yes, using a time-tested textbook is imperative—especially for learning the fundamentals of Japanese grammar. I used a series called Everyday Japanese, which is still very much of a gold standard. While grammar is essential, I would encourage you not to get too bogged down in the particulars of when, for example, to use wa (は) vs. ga (が) or de (で) vs. ni (に), because it will drive you crazy! Like how in real estate, the key to success is “location, location, location,” to master a foreign language, it boils down to “vocabulary, vocabulary, vocabulary.” After memorizing a certain number of words, the rest will come naturally, and you will find that it becomes possible to achieve steadily higher plateaus of fluency. Without an ever-growing vocabulary, you will, though, continue to struggle.

9. Try to avoid romaji

Especially if you are from the West, it is highly likely that your first exposure to formal Japanese instruction will include words written in romaji (ローマ字), the “romanization” of Japanese sounds by using Latin letters. We have an American missionary who used to reside in Yokohama called James Curtis Hepburn to thank for this system, which dates from 1886. While it is probably not possible for a Westerner simply to jump into the study of Japanese without romaji, as a long-time student of the language, I would strongly encourage you to do everything possible to avoid relying on it. Try to wean yourself off the bad habit of using romaji as soon as possible, because it will hold you back. Especially when encountering gairaigo (外来語), foreign words that have been “Japanized,” this will be somewhat of a challenge. To accelerate your ability to read and write Japanese like a native, you should, though, try exclusively to use hiragana, katakana, and kanji just like Japanese schoolchildren.

10. Keep a journal to record vocabulary

Like other parts of Asia, Japan is a land with lots of outdoor signage. Thus, you can find new words to study simply by walking down the street. Jot down these words in a notebook even if you are not sure of the proper stroke order; The act of writing is key. If possible, use a dictionary—either a digital app or an old-fashioned paper dictionary—to look up each new word right away. Each time you get a list together, make flashcards to practice and commit to memory your new vocabulary. While it is okay to use electronic flashcards, it would, ideally, be best to make your physical flashcards. Yes, it takes extra work, but this is the best way to learn. Japanese elementary and middle school students routinely do this. Thus, it is relatively easy to find a set of approximately 50 or so blank mini flashcards held together by a metallic ring at most stationery stores in Japan. I used to make my own flashcards and practice while riding the subway to get to school.

I will, in fact, never forget the cathartic experience I had one day while riding a train and finally realizing that the characters used to write kyuko in Japanese (急行) mean “express train.” Up until that point, I had been riding the local or kakuekidensha (各駅電車), which made a stop at every station. From that day, I learned how to navigate by the express, which shaved a good thirty minutes off of my commute. It is a prime example of the power of vocabulary.

11. Yes, stroke order matters!

Many of the words that you will need to commit to memory are written in kanji or the Chinese characters, which were incorporated into the Japanese language approximately 1,500 years ago. Kanji are to be written with specific stroke order, and, yes, it matters. Learning to write kanji with the correct stroke order can be tedious, but your writing will be more legible if you take the time to do it right. A useful, relatively inexpensive tool that you can use to practice stroke order and learn more vocabulary is a kanji practice book designed for Japanese school children. They start with the basics for 1st graders. If you are beginning your formal study of Japanese at age 18, for example, like I did, then swallow your pride and make a small investment in some of these books—beginning with the lowest level—and a set of pencils. It will seem like you will be writing the equivalent of “I will learn kanji” a thousand times on a blackboard, but you will make progress. Yes, this is literally “old school,” but the act of writing (in the proper stroke order) is what is essential. You will find that before long, you will have reached a new learning plateau and be ready for the next challenge. Hey, you may even “graduate” from elementary school after a year or so!

12. There’s an app for that!

While your formal class will probably be structured around some sort of an electronic system for keeping track of assignments, tracking vocabulary, etc., using an app or online system for recording your progress on your own is critical. There are many available, but I have found that the web-based platform called Kanshudo (www.kanshudo.com) works best for me. Even after more than 30 years of studying Japanese, I still make it a point to continue to learn new vocabulary, reinforce grammar concepts, etc. with this system daily. It doubles as an extensive, online dictionary that can automatically generate electronic flashcards. At a glance, you can chart your progress along with several dimensions. To gain access to the full site, you should pay an annual fee of US $30, and it is well worth it.

13. Learn by watching NHK and Netflix

While both offer only a one-way learning experience without any feedback, two other useful electronic teaching aids are NHK’s Sign Language News 845 (NHK手話ニュース845) and the language learning extension for Netflix. NHK is Japan’s national television broadcasting agency, and they produce a short, daily summary of current events designed for Japanese people who cannot hear. While the original intent of this service, delivering the news with sign language, is not all that useful for us students of Japanese, the pace is, in general, a little slower than the delivery of the regular news. On the right side of the screen, the day’s headlines are summarized in short sentence format complete with furigana (ふりがな) which are used to read kanji characters. While you can see this program on live television, it is also posted on NHK’s website.

14. Progress before Perfection

While the old saying “practice makes perfect” certainly applies, do not get frustrated along the way, as you will never, in fact, become perfect—but that’s okay. Just keep practicing! Like learning any foreign language, attaining fluency in Japanese is very much of a journey vs. a destination, and there is always going to be more that you can do to increase your facility with the language.

Conclusion

While you are likely to face many humbling moments when you may even second guess your decision to study Japanese, the reward of being able to communicate with Japanese people will be well worth the effort. Also, feel free to add to the comments any useful tips not mentioned above. This article is only meant to be a starting point.

Related Articles

AI Girlfriends: Exploring the World of Virtual Companions

AI-generated girlfriends are growing popular on Japanese Twitter. Learn more about what they can do, and what it could mean for the future.

Discover Japan’s Top 10 Must-Visit Places

From stunning landscapes to bustling cities, Japan offers many unforgettable experiences. Here are Japan’s top 10 best places to visit!