A candid, true-life story of how an American became a foreign “salaryman” in Japan

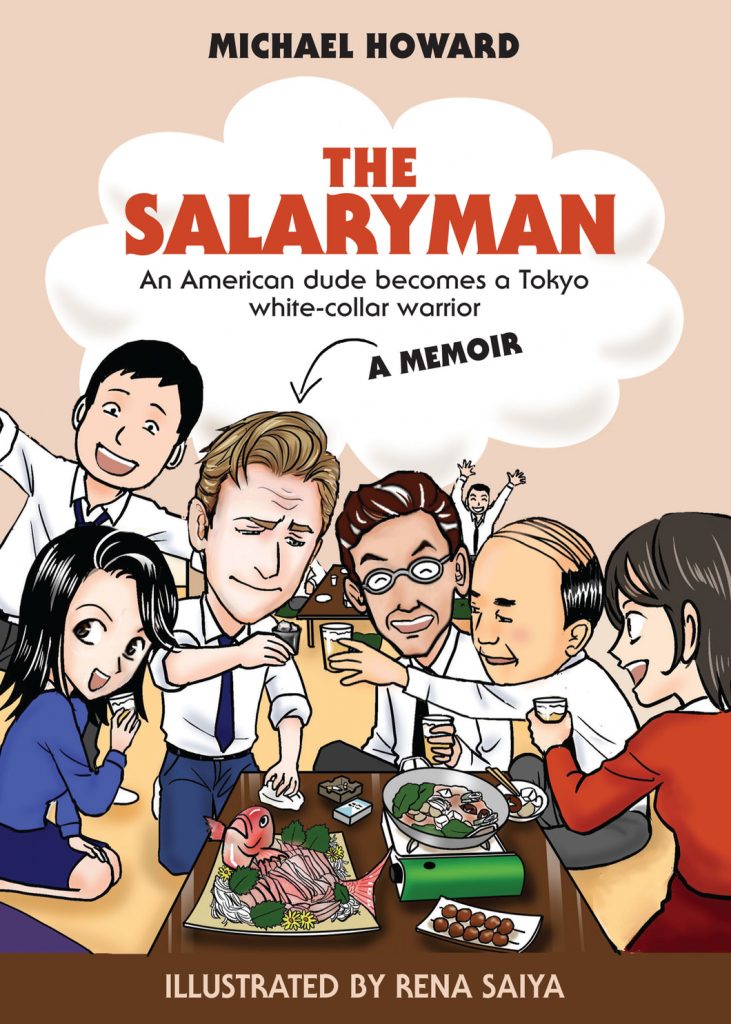

Review of The Salaryman: An American Dude Becomes a Tokyo White-Collar Warrior

For all non-Japanese—and especially for Westerners–who may be contemplating a career at a large-scale Japanese company while working in Japan, Michael Howard’s The Salaryman: An American Dude Becomes a Tokyo White-Collar Warrior, A Memoir is essential reading. It is a candid and, at times, somewhat cynical view of how large, traditional Japanese enterprises work. Peppered throughout with amusing personal anecdotes, you will enjoy reading Mr. Howard’s thorough account of the often absurd facts of life for a foreigner working within such an environment.

First, you need to become familiar with the wa-sei eigo (Japanese English) term “salaryman.” The salaryman is used in the Japanese language to describe a typical, white-collar “company man” (almost always male.) He is extremely loyal to their employer that is usually a large Japanese company with a long heritage. These are the stereotypical Japanese businessmen who have been the stalwart representatives of Japan, Inc. since Japan’s economic miracle began during the 1960s.

They typically join their firm right of college and stay through retirement, unless they succumb prematurely to karoshi or “death from overwork.” Although he did not initially set out to do this, when Mr. Howard agreed to switch jobs and re-locate to Tokyo from a California-based company, the author became his Japanese employer’s very first American salaryman. He was subsequently forced to conform to the vastly different style of business in Japan, and this book is Mr. Howard’s detail accounting of his experience.

Based upon Mr. Howard’s accurate descriptions of all sorts of peculiar situations that I have also experienced during my 20+ years of living and working in Japan, I can definitely vouch for the authenticity of this real-life story that was based upon the author’s keen observations during his eight years of working for a number of Japanese employers in the Greater Tokyo Metropolitan Area. Since we are almost the same age and both share the same hometown of Chicago, I could really relate to Mr. Howard’s commentary about how different life is back in the U.S. While I would not want to spoil anything for you, here are my impressions of a few of Mr. Howard’s insights that particularly resonated with my own experience.

Inability to See the Forest for the Trees

The author is correct when he states that you will often hear the Japanese term “mottanai” mentioned in exasperation as a typical response to perceived wasteful behavior. It can be used whenever your children seem to have trouble finishing something on their plate, but the appropriate usage of this word extends far beyond the dinner table. Japanese are well known as champions of continuous improvement (kaizen or 改善 in Japanese), and this cult of the pursuit of perfection and efficiency is often rigorously applied toward cost-saving activities in a Japanese office.

Sometimes it can, however, be taken too far. For example, Mr. Howard cites how one of his superiors was particularly keen to save money. This boss ordered his staff to avoid making photocopies, but instead, scan and print-out documents because the cost of using a computer printer was a few yen less than the cost of using a photocopier. Mr. Howard effectively highlighted how this enthusiasm taken to the extreme could often morph into being “penny-wise, pound-foolish.”

I routinely encountered this type of situation and the application of extreme attention to detail at the expense of a greater appreciation of the big picture. While the performance of salespeople is primarily assessed based on net new revenue growth at virtually any company, most sales organizations also judge their sales team based on a variety of other criteria. No matter how each metric is weighted, you can be certain that the savviest salespeople will be acutely aware of how to optimize each component of their compensation. Sometimes this can lead to less than ideal results that skew overall performance.

Although hardly unique to Japan, in my experience, some salarymen would focus too much attention on relatively unimportant call metrics just for the sake of getting full credit for the achievement of a milestone with low value even at the expense of spending time on opportunities to drum up and close new business. The best sales associates would, however, first ensure that their overall numbers were solid before focusing on minor goals. The worst performing members of the sales team would, though, frequently fall into the trap of not being able “to see the forest from the trees.” In detail-obsessed Japan, I, too, constantly had to fight off the influence of the people around me who often seemed too focused on minor details and, instead, take a step back from time to time to gain a broader perspective.

Hesokuri “Secret” Fund

Mr. Howard keenly noticed how a Japanese salaryman would often be forced to channel their creativity and a great deal of their time into working around the rules (typically those imposed by Human Resources) to game the system. One of the excerpts that sounded particularly familiar was the author’s detailed description of how a salaryman would fund their hesokuri or secret fund for personal entertainment. Although there is a growing trend to abandon this practice, most Japanese companies still pay their employees a flat-fee allowance for business trips rather than simply reimburse them for actual expenses like it is the norm in the West. As a means for generating a little extra spending money, a salaryman will, as a result, try to stay at a budget hotel, conserve meal expenses when eating alone by ordering cheap take-out food from a convenience store, and subsequently pocket the difference.

For most of my career in Japan, I worked at the Japanese subsidiary of an American company. As we essentially took over the business of our original Japanese distributor more than 20 years ago, from the start, we simply adopted the existing work rules, including Japan’s extensive system of allowances. While it took a few years before the internal audit team of my firm’s American headquarters fully understood this practice, when they did, the auditors tried to make it their mission to get rid of this perceived wasteful practice and have the Japanese subsidiary convert to reimbursing actual expenses. After the first audit, I dutifully tried to reason with our Japanese managers but recall their visceral reaction equivalent to “over my dead body” after simply suggesting this possibility. I was immediately schooled about the related, common practice called hesokuri that Mr. Howard outlines in great detail, the practice of allowing a salaryman to receive direct deposits for their allowances into a separate bank account from the one used to pay their salaries.

Keep in mind that the purse strings in many Japanese homes are controlled by the spouse of a salaryman. A typical salaryman receives a meager allowance after “turning over” their salary to their spouse each month. To augment this insufficient allowance, a salaryman relies heavily upon the “secret” source of funds, his hesokuri. When not on an expense account they typically use this income to spend on drinking and karaoke parties with colleagues, to buy cigarettes, to play pachinko, and in some cases to support a covert habit of frequenting soapland (another wa-sei eigo (Japanese English) term for “massage parlor”). Any policy to do away with the flat-rate travel allowance and simply reimburse actual expenses would, therefore, be a direct assault on a salaryman’s all-important hesokuri fund. For years I was, luckily, able to hold off the auditors by explaining that any attempt to do away such allowances would result in a full-scale mutiny. Mr. Howard provides more details and does a great job of explaining how he was taught to maximize his hesokuri fund.

Drinking

While there are plenty of exceptions to the rule, Japanese people have, in general, a reputation for a fondness for alcohol combined with a limited capacity to hold their liquor. The internet is plastered with photos of drunk Japanese salarymen passed out (and sometimes only partially clothed) in the middle of a late-night subway. Especially on a Friday evening, it is not uncommon to see large numbers of drunks staggering around the busy train stations of Tokyo.

Japan’s binge-drinking culture is sacrosanct for the salaryman. Mr. Howard certainly seems to have gotten a lot of practice with this particular aspect of his salaryman training. He succinctly summed it up as “…the izakaya (Japanese pub) two-hour all-you-can-drink course is a true salaryman special. After getting drunk, smoking is the second priority, with actual food being tertiary.” I fully endorse this vivid description. Mr. Howard goes deeper, though, to explore why this seemingly wild behavior is an essential safety valve to counter-balance the immense pressure always to abide by the regulations of everyday office work and conform to the all-pervasive, strict rules of Japanese etiquette. Mr. Howard accurately observed that the salaryman undergoes a “Jekyll and Hyde transformation from formal rule-followers to jolly dinner companions” instantaneously when they step into an izakaya. In this environment, hierarchical authority tends to become blurred in stride with each successive drink.

My Best Drinking Party

As a Westerner working in Japan, the willingness to let down one’s guard while partying can be quite refreshing. Although it took place more than 15 years ago, the best party with work colleagues in Japan that I ever experienced was a company-wide outing to Hakone, where we gave everyone an allowance in advance to prepare a unique costume. While many–including me–procured their evening attire from Don Quixote, which has a dedicated costume section, there were some extraordinarily creative and risque homemade creations. The first president of our Japanese subsidiary, normally a well-dressed model salaryman in his mid-fifties at the time, led by example by going in drag and donning a full bodycon (tight-fitting) China dress and wearing blue eye shadow and hot pink lipstick. After a lively costume show complete with voting and prizes, everyone proceeded to get roaring drunk. To this day, those that participated in that raucous evening still talk about it–particularly how it brought together absolutely everyone regardless of rank. (By the way, I went as a sumo wrestler.) Don’t worry–not every night is likely to be so wild!

Like Mr. Howard, if you are the sole foreigner at the party and especially if you are a manager, you do need to be aware that you will, most likely, be given special attention. While hardly a heavy-weight, as a typical, middle-age Western guy, I can hold my own with the seemingly endless succession cheers of “kanpai” (“cheers” in Japanese which means “bottoms up”). Especially after becoming the president of my former organization in Japan, I consciously kept track of just how many times my glass was topped off by what always seemed like everyone in the room. After a point, it is okay to refuse yet another round of “kanpai,” but you must be careful not to offend any of your well-meaning drinking partners. While some refuse to drink at all, drinking to excess is, for all practical purposes, an essential part of fitting in as a salaryman in Japan. It is, therefore, best to assume that these activities will simply be part of the job.

Conclusion

Becoming a Japanese salaryman is not easy for a typical foreign (especially Western) business person. Navigating through seemingly nonsensical bureaucracy and dealing with an almost blind insistence to follow the rules was undoubtedly out of character for Mr. Howard. Although he certainly endured a great deal of frustration along the way, Mr. Howard relied upon his sense of humor to stick it out. In the end, he was– especially from his mentors—definitely able to glean some valuable insights from this experience which has, undoubtedly, made Mr. Howard is more adept at relating to his Japanese counterparts both across the negotiating table and at the water cooler. The Salaryman: An American Dude Becomes a Tokyo White-Collar Warrior, A Memoir is an excellent read for any aspiring salaryman.

You can learn more about Japanese business etiquette by reading my past article “Mind Your Manners: Top Ten Pointers for Mastering Japanese Etiquette.”

Related Articles

Japan’s Maglev Train Project Faces Setbacks in Shizuoka

The President of JR Tokai, Shin Kaneko, has stated that it will be impossible for the maglev train to open by 2027 due to the ongoing issues in Shizuoka.

Major Japanese Retailers Step up Support for Ukrainian Refugees

Japanese corporations such as Don Quijote, Muji, and Uniqlo are behind major relief efforts to help displaced Ukrainian refugees.